My son’s last day in a classroom was one year ago today. At the time we thought that in-person schooling would pause for a few weeks or maybe even a month or two. When June rolled around, we figured that, certainly, he’d be back in the classroom by the fall. Today is March 13, 2021 and he still hasn’t returned to school in-person. Neither have I and neither has my husband. We’ve all been Zooming around the house for the last year. With all of us either teaching online or learning online, I got to thinking about what those of us who have been teaching online have also learned.

When we first shifted to remote pandemic teaching, there was a big push to learn about apps, programs, and other technologies to engage students. Teachers learned how to use GoogleClassroom, GoogleMeet, Jamboard, Flipgrid, Padlet, and of course Zoom. They scrambled to organize online classroom space and to connect with students in a stressful and ever-changing situation.

When the fall term rolled around, educators had a handle on the online teaching thing. They had the summer to regroup, but the uncertaintly of what the 2020-2021 school year would look like persisted. Would schools open for in-person teaching? When might that happen? What would that look like? The school year dragged on and here in California case rates seemed to drop, but then soared well above where we had previously seen them. Finally, with just over a quarter of the school year remaining, we are talking about returning to some kind of in-person instruction–but to be fair–we are not returning to school as we knew it–I have to wonder what we have learned and what practices and technologies we will continue to use moving forward.

The problems with online teaching and learning have been widely covered in the news and all across social media. We all seem to be well aware of the struggles teachers, students, and parents have experienced.

That said, there are some positives to come out of remote pandemic teaching and learning.

Teachers and students have learned new ways of communicating, learning, and creating. I have been asking educators and students what they hope to continue doing or using when they return to in-person teaching. The responses have ranged from simple practices, like posting agendas and class notes to GoogleClassroom (or whatever learning management system (LMS) they are using), so that students who are absent can review what they missed. Teachers are posting slide decks they use for in-class presentations on the LMS. This is such a simple idea that supports students. But, this also seems to be a practice that would also help all students, not just those who missed class. After all, why shouldn’t they be able to access the slide deck in case they want to review it later? Really, this is something we could have been doing pre-pandemic. But, sometimes we need a nudge.

Posting everything to the Google Classroom with links and docs and slides in case a student misses a day.

— Melanie White is learning from #DisruptTexts (@WhiteRoomRadio) March 8, 2021

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Another response I received talked about how students have been using (because their students are back in the classroom) GoogleMeet for group collaboration with a student who was absent.

My kids had group projects they were working on. One person was absent so they logged on with her in a google meet to keep working. It was great!

— Kim Dunnagan (@MrsKDunnagan) March 9, 2021

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Other educators have embraced using tools that allow for digital collaboration like Jamboard and Padlet. These apps can be used to continue the conversations we have in class, much like discussion boards can be used in the same way. Even when students return to class, tools like FlipGrid and WeVideo allow students to show their content knowledge (and personalities) in video form.

@WeVideo for instructional videos and student video creation.

— Michael Pothast (@potter1938) March 8, 2021

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Perhaps some of the most basic things teachers will bring to their classrooms is a digital classroom that contains resources and assignments all in one place. It’s not very glamorous or earth-shaking, but it IS very helpful for students. And while many teachers were already using GoogleClassrom or some other LMS for this purpose, after pandemic teaching, it would seem that more would be in the habit of organizing this information–notes, slide decks, digital “handouts,” assignments and such in a clearly organized way so that students can quickly locate what they are looking for. It’s also helpful for teachers who don’t have to organize quite so many stacks of papers. Online tools also typically give teachers access to data revealing where students struggle, too.

@gimkit my kids love beat the boss with me as the boss and trust no one.

— Kyle French (@MrFrenchTeaches) March 8, 2021

No papers turned in, all online. It’s quicker to grade and I just take home my computer.

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Pandemic teaching pushed educators into a vulnerable and uncomfortable position in which we had to try new things and risk failure . . . in font of our students. Isn’t that great! I mean, really, we ask our students to do things that are new, uncomfortable, and that cause them to feel vulnerable all the time. Isn’t is good to put ourselves in their shoes in this way. It has also been humanizing in a way that we might not have expected. When we try something and fail, but adjust and try again, that process in and of itself is a valuable message to students. After all, most of us try to hide our failures from students. Hopefully, this bravery in innovation will stick.

For many years prior to the pandemic, the concept of the flipped classroom was widely discussed. And while many teachers used this model, many others were intrigued but found the idea of creating their own videos to be daunting. Now many teachers have gained experience in making videos and are positioned to flip their classrooms upon returning to in-person teaching. Just the experience and practice making videos themselves is something that teachers are likely to continue doing. Short video tutorials for example, are useful for students to review even when more traditional models of education return. This practice also helps teachers support students when they are asked to create videos of their own–another practice that is likely to continue.

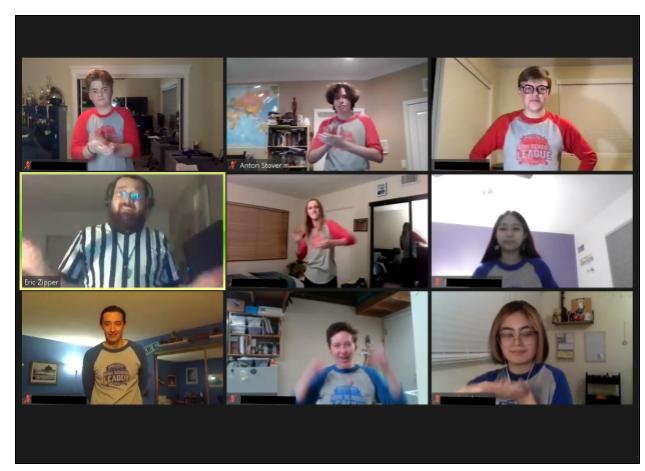

Despite all the challenges, educators have come up with some really incredible creative solutions. North High School dance teacher, Coral Taylor put on the annual dance show even when there was no in-person school. Students choreographed and recorded their numbers mostly separately. A few recorded in an empty parking structure. They edited their pieces and the show was streamed live on YouTube. My son is on the ComedySportz team at his school. ComedySportz is an improv competition. How can that possibly happen remotely? Over Zoom, of course. And the best part was that family and friends on the other side of the country could watch, too.

We cannot talk about what we have learned in the era of pandemic teaching without exploring the vast inequities that have been thrown in the limelight. We should have known these inequities existed all along, and many teachers were acutely aware of the struggles their students experienced. Anyone who, at this point, believes that all students have access to devices, broadband internet, and a quiet space to work at home has their head in the sand. Add to that the vast number of students who also may not have supervision at home or who experience food insecurity on a regular basis, and it becomes clear that A: schools provided many more services than “simply” educating students and B: the time has come to tackle these inequities in our communities. There should be no looking back on these issues.

There is no doubt that this last year has been rough on students, teachers, and parents. But, maybe among the shifts and the problem-solving, educators have also been able to reflect on their practices and determine what matters most in their interactions with students. I can only hope that this is the case and that this will lead to a real shake up in education like nothing we have seens in our lifetimes. We have an opportunity here to narrow equity gaps, to encourage self-discipline in students, creativity, problem-solving, and innovation. While we may be excited at the propect of moving back to in-person schooling, let us internalize the lessons of the last year. We can’t go back to the way things were and we shouldn’t even try.